“I do not wish my anger and pain and fear about cancer to fossilize into yet another silence, nor to rob me of whatever strength can lie at the core of this experience, openly acknowledged and examined ... imposed silence about any area of our lives is a tool for separation and powerlessness.” – Audre Lorde, The Cancer Journals (1980, 9) I first got diagnosed with breast cancer in January 2021. My first reaction was, of course, crying and talking with my family. My next reaction was turning to read familiar and comforting words: Audre Lorde’s The Cancer Journals (1980). There was something about reading the words of another Black woman who had gone through the journey on which I was about to embark that bolstered me. Audre Lorde opens the book by identifying herself as a “post-mastectomy woman who believes our feelings need voice in order to be recognized, respected, and of use” (9). I, too, am a “post-mastectomy woman.” But it was quite a whirlwind to get to that point. It all started with a routine mammogram. I had no lumps or symptoms of any kind. I was 41 and had my first mammogram 3 years prior. Usually, people start getting mammograms at 40, but I started a few years earlier because I had dense breast tissue that sometimes felt lumpy. Ever since then, getting mammograms was just something that I did every year out of habit. About a week after the mammogram, I got a call-back to do a diagnostic mammogram. I had to wait a month for an appointment. My husband accompanied me to the diagnostic mammogram appointment. I was glad he did, because afterwards the doctor called us into a room and said that they saw calcifications on my right breast that were concerning. She said I would need to have a stereotactic core needle biopsy, so I scheduled that for the following week. By the end of the week, I got a call from my primary care physician. My heart sank when I saw her name on my Caller ID. I knew she would only be calling me for one reason. She told me that I had a Ductal Carcinoma In Situ (DCIS), an early stage non-invasive breast cancer that is localized in the milk ducts. “If you have to get breast cancer, it’s the kind you want to get,” my doctor said. I thought that was an odd thing to say, but those words would later give me a strange sense of comfort. When I received this jarring news, I was home by myself with my 5-year-old son. I felt like the room was spinning and closing in on me as I struggled to figure out what my next step should be. “I wanted to write in my journal but couldn't bring myself to. There are so many shades to what passed through me in those days. And I would shrink from committing myself to paper because the light would change before the word was out, the ink was dry” – Audre Lorde, The Cancer Journals, p. 45) For the next few days, I felt like I was in a fog, even as I showed up to Zoom retreats and meetings. Like Audre Lorde, I wanted to write in my journal, but I was too overwhelmed to do so. The news was too fresh and too raw to share with colleagues, but it was all I could think about. Life kept going at break-neck speed with Zoom presentations, meetings, and classes. I was chairing a department, supervising remote school for my kindergartener, and teaching two classes. If that weren’t enough, my family was also in the process of selling our old house, buying a new one, and moving across town. We closed on two houses and moved about a week after my diagnosis. When I met with the breast cancer surgeon, he told me that the treatment plan for DCIS usually consisted of two options: 1) lumpectomy followed by radiation and taking hormone blockers for 5-10 years; or 2) a single or double mastectomy. However, he explained that I would need additional testing to determine which treatment plan would be suitable. For the next four months, my schedule became packed with calls, surgical consultations, biopsies, MRIs, genetic testing, and research. Having breast cancer and trying to figure out what to do about it was becoming like a part-time job. When I finally had the breast MRI in late February, I was shocked to learn that they found additional suspicious spots on both breasts. However, the MRI is so sensitive that it can easily detect abnormalities without being able to discern if they are cancerous or not. This meant I had to get more biopsies to investigate. One day in mid-March, I spent almost an entire day (8am-2:30pm) at Winship Cancer Institute having my body contorted into all kinds of awkward positions and my breasts poked, prodded, squeezed in three different types of biopsies! The fact that I had to wait 10 days until my follow-up appointment with the surgeon to go over the results of the MRI was horrible for my anxiety. It turned out, there was good news and bad news. The good news was that the spots on the left breast weren’t cancerous, but they would have to be monitored with further imaging every six months. The bad news was that the spots on the right side were more DCIS in a separate location from the original area. This meant that lumpectomy was no longer an option. It was official: I would need to have either a single or a double mastectomy. It was stressful to have so many major decisions to make that would have such a huge impact on my life. Single or double mastectomy? Breast reconstruction or aesthetic flat closure? If I chose reconstruction, should I get implants or do autologous tissue reconstruction like Diep Flap? In Diep Flap reconstruction, the surgeon takes tissue from your stomach and uses that to rebuild your breasts. Ultimately, I chose a double mastectomy after extensive research and discussion with my surgeon because I had several risk factors for getting breast cancer again. One decision done. However, I was torn over the decision between breast implants or Diep Flap. After lots of research and surgical consultations, I chose Diep Flap reconstruction. At long last, I had a plan – I would have a double mastectomy and immediate Diep Flap reconstruction on May 4. But you know what they say about plans… “I needed to rally my energies in such a way as to imagine myself as a fighter resisting rather than as a passive victim suffering.” – Audre Lorde, The Cancer Journals, p. 73 On my surgery day, due to unforeseen circumstances beyond my control, I was unable to do immediate Diep Flap reconstruction. Instead, my surgeon said he would do the double mastectomy and put in tissue expanders, and then I would have reconstruction three months later. I had hoped to be “one and done” with surgery so that I could get back to my normal life, but the universe had other plans. The surgery lasted 4-5 hours and I stayed overnight in the hospital and went home the next day. They also had to take lymph nodes from my right side to determine if the cancer had spread. Luckily, it had not. When the pathology report came back, it showed that the surgery had removed all of the cancerous tissue. This meant that I was officially cancer-free, and I would not need chemotherapy or radiation! “Now I was going to have to begin feeling, dealing, not only with the results of the amputation, the physical effects of the surgery, but also with examining and making my own, the demands and changes inside of me and my life. - Audre Lorde, The Cancer Journals, p.46 It was very difficult to look at myself in the mirror in the first weeks after surgery. I cried the first time. I felt like I had undergone an amputation. The hard, plastic expanders felt heavy and uncomfortable. Each week, I had to go to the surgeon’s office for saline fills, where he stuck a needle into my chest to fill the expanders so that it would create a pocket to be used during reconstruction. Every time, my chest felt tight and painful. I also had to go to physical therapy twice a week and do exercises every day at home to regain the ability to raise my arms above my head and reach behind my back. I had my physical therapist take a picture of me on the day that I could finally raise both arms above my head – July 20 – two and a half months after my mastectomy! On August 10, it was time for my breast reconstruction surgery. The surgery took 11 hours, and there were two surgeons and two surgical residents operating on me. I had to stay in the hospital for four days. For the first 24 hours after surgery, I had a morphine pain pump, and nurses had to check the blood flow in my new breasts every hour. Due to Covid, I was allowed two family members who could visit, but one at a time, so my mom and husband took turns visiting me and staying overnight. Getting in and out of the hospital bed for the first time was a seemingly impossible and very painful feat! I needed two people to help me out of bed, and then when I was getting back into the bed, the nurse grabbed my legs and threw me to “get it over with quicker.” I screamed out in pain. For the first two weeks after surgery, I had to walk hunched over and use a walker. Of course, that caused immense lower back pain. I also had to sleep in a power lift recliner for several weeks after each surgery. As I write this reflection on what I have endured in the last ten months, I am grateful for this journey and counting my blessings. I was extremely lucky that my cancer was caught early. I was lucky that I did not need to do chemotherapy, radiation, or hormone blockers. I was lucky to avoid any major complications from the surgeries. I am fortunate and immensely grateful to have family and friends who have rallied around me. They sent flowers, Grubhub gift cards, and things that I would need for my recovery from my Amazon Wish List. My mom and aunt, who are both nurses, spent two weeks each with me after both surgeries, and several friends came to visit me as well. Thanks to the Family Medical Leave Act (FMLA), I was able to take four weeks off from work after my mastectomy, and eight weeks off after my reconstruction. I am now eight weeks post-op, and it has been a slow process. When I get impatient, I have to remind myself that my body is literally stitching itself back together from the inside out. I have been prioritizing rest and meditation like never before. I wanted to share a bit of my story during Breast Cancer Awareness month to encourage women – especially Black women who have higher mortality rates from breast cancer – to make sure to get your routine mammograms and do your self-breast exams. Do not wait or put it off because of the pandemic or because you’re too busy or because you put everyone else’s needs before your own! Mammograms literally save lives. They certainly saved mine. For Further Reading on Breast Cancer and Black Women: https://healthmatters.nyp.org/what-black-women-need-to-know-about-breast-cancer/ https://www.breastcancer.org/research-news/black-women-added-to-high-risk-group#:~:text=While%20overall%20rates%20of%20breast,cancer%2C%20and%20differences%20in%20healthcare. https://www.bcrf.org/blog/black-women-and-breast-cancer-why-disparities-persist-and-how-end-them/

1 Comment

Houston, TX, USA. 8th June, 2020. Members of the Yates High School championship football team speak during a candlelight vigil honoring George Floyd on Monday, June 8, 2020, at Jack Yates High School football field. Credit: Karen Warren/ZUMA Wire/Alamy Live News Credit: ZUMA Press, Inc. / Alamy Stock Photo Jack Yates, George Floyd, and Juneteenth This year’s 148th celebration of Juneteenth in Houston’s Emancipation Park resonates with new meaning. Typically, the celebration draws thousands of residents and visitors to Houston’s Third Ward annually. However, because of COVID-19, the parade and day-long slate of outdoor activities have been replaced with a robust program of events that will be streamed around the world. Just a few weeks ago, such a shift would have been monumental. But then, thousands of miles from his hometown and beloved Third Ward community, a police officer killed George Perry Floyd, Jr, ignoring his desperate cry, “I can’t breathe.” As video of Floyd’s death circulated on television and social media, a city, then a nation, and, finally, a planet shook as mourners took to the streets to express their collective grief and anger about yet another black life stolen on the flimsiest of pretenses. Floyd’s tragic and untimely death appears to be sparking a new black freedom movement that is reverberating globally, layering new meaning onto one of the longest running and most iconic black freedom celebrations in the United States: Juneteenth at Emancipation Park in Houston, Texas.  Caption: Juneteenth Celebration, Emancipation Park. Jack Yates is on the far left. Credit: MSS 0281-0053 Jack Yates Antioch Baptist Photograph Collection, Houston Public Library, African American Library at the Gregory School. Caption: Juneteenth Celebration, Emancipation Park. Jack Yates is on the far left. Credit: MSS 0281-0053 Jack Yates Antioch Baptist Photograph Collection, Houston Public Library, African American Library at the Gregory School. Juneteenth is a uniquely African American holiday. It commemorates June 19, 1865. On this day, in Galveston, Texas, Union Army General Gordon Granger publicly read Abraham Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation and declared to all Texans, black and white, that slavery was no longer the law of the land. This act took place a full two months after the South formally surrendered in Appomattox Court House, Virginia on April 9, 1865. Juneteenth celebrations in Emancipation Park can be traced back to 1872. That year, an interdenominational group of African American church leaders got together to purchase land near their churches to create a public park for their Houston community. This park, which they named Emancipation Park, served an important function in the community. Although free from slavery, African American enjoyment of freedom was often curtailed by white authority through segregation and exclusion laws and also surveillance of their actions. Barred from public parks in the city, they banded together and purchased their own space to gather for leisure and community. From the very beginning, Juneteenth celebrations in Emancipation Park were carefully organized and well-attended affairs. In addition to the annual parade, there were Miss Juneteenth contests, speeches, music, pageantry, dancing, and prayer.  Caption: Pictured is a buggy decorated for the annual Juneteenth Celebration. In the buggy are Jack Yates’ daughters, Martha Yates Jones and Pinkie Yates. Prominent families, organizations and institutions would decorate jitneys or buggies with flowers, parade them around the community, and end up in Emancipation Park for a celebration. Credit: MSS 0281 Jack Yates Antioch Baptist Photograph Collection, Houston Public Library, African American Library at the Gregory School. Caption: Pictured is a buggy decorated for the annual Juneteenth Celebration. In the buggy are Jack Yates’ daughters, Martha Yates Jones and Pinkie Yates. Prominent families, organizations and institutions would decorate jitneys or buggies with flowers, parade them around the community, and end up in Emancipation Park for a celebration. Credit: MSS 0281 Jack Yates Antioch Baptist Photograph Collection, Houston Public Library, African American Library at the Gregory School. A fixture at these Juneteenth celebrations was former slave and Baptist minister John Henry Yates. Known by all as “Jack,” Reverend Yates was among the group of community leaders who pooled their resources to create Emancipation Park. Yates was a dedicated family man and a pillar of his community. He helped establish Antioch Missionary Baptist church, Bethel Baptist church, and Houston Academy, a school for African American children. Yates died in 1897. In 1926, when Houston’s second high school for African-Americans was opened, his beloved community named the school after him. George Floyd graduated from Jack Yates High School, where he played football and basketball. Although he was born in North Carolina, he spent most of his forty-seven years in Houston. It is not difficult to imagine him together with his friends and family taking part in the annual Juneteenth parade and its accompanying festivities in Emancipation Park. A towering figure, Floyd was well known in his community. After two years away in college, Floyd returned home and worked hard to find his footing. His path was not easy or straightforward. He served time in prison for drug possession, theft, and aggravated robbery. However, upon his return home, he committed himself to healing his community through faith practices. On Sunday mornings he could be seen setting up chairs and tables for church services on a neighborhood basketball court. Eventually, he moved to Minnesota in search of a fresh start. Although separated by time, Jack Yates and George Floyd are forever connected by place. Third Ward, the community that Yates nurtured, in turn nurtured Floyd. They walked the same streets. They participated in the same rituals to commemorate the abolition of slavery and to celebrate black freedom. Whether he realized it or not, as he matured, Floyd also followed in Yates’s footsteps by community-building through faith. And since March 25, 2020 they are linked in a new way. During his lifetime, Yates self-consciously participated in African American struggles for freedom. In the weeks following his death, George Floyd’s name and his final words, “I can’t breathe,” have become rallying cries in a renewed movement, global in scale, for black freedom. Listen to Cite Black Women's podcast interview with Dr. Stuckey here on Soundcloud. Suggested Readings Arica L. Coleman, That the Blood Stay Pure: African Americans, Native Americans, and the Predicament of Race and Identity in Virginia, Indiana University Press, 2013 Brittney C. Cooper, Beyond Respectability: The Intellectual Thought of Race Women, University of Illinois Press, 2017 Deirdre Cooper Owens, Medical Bondage: Race, Gender, and the Origins of American Gynecology, University of Georgia Press, 2017 Kendra Taira Field, Growing Up with the Country: Family, Race, and Nation after the Civil War, Yale University Press, 2017 Shennette Garrett-Scott, Banking on Freedom: Black Women in U.S. Finance Before the New Deal, Columbia University, 2019 Sarah Haley, No Mercy Here: Gender, Punishment, and the Making of Jim Crow Modernity, University of North Carolina Press, 2016 Kellie Carter Jackson, Force and Freedom: Black Abolitionists and the Politics of Violence, University of Pennsylvania Press: 2019 Karla Slocum, Black Towns, Black Futures: The Enduring Allure of a Black Place in the American West, University of North Carolina Press, 2019  Dr. Melissa N. Stuckey is assistant professor of African American history at Elizabeth City State University (ECSU) in North Carolina. She is a specialist in early twentieth century black activism and is committed to engaging the public in important conversations about black freedom struggles in the United States. Dr. Stuckey is the author of several book chapters, journal, and magazine articles including “Boley, Indian Territory: Exercising Freedom in the All Black Town,” published in 2017 in the Journal of African American Historyand "Freedom on Her Own Terms: California M. Taylor and Black Womanhood in Boley, Oklahoma" (forthcoming in This Land is Herland: Gendered Activism in Oklahoma, 1870s to 2010s, edited by Sarah Eppler Janda and Patricia Loughlin, University of Oklahoma Press, 2020). Stuckey is currently completing her first book, entitled “All Men Up”: Seeking Freedom in the All-Black Town of Boley, Oklahoma, which interrogates the black freedom struggle in Oklahoma as it took shape in the state’s largest all-black town. Stuckey is also working on several public history projects. She has been awarded grants from the National Parks Service and the Institute for Museum and Library Services to rehabiliate a historic Rosenwald school on ECSU's campus and to preserve the history and legacy of these important African American institutions. In addition, she is a contributing historian on the NEH-funded “Free and Equal Project” in Beaufort, South Carolina, which is interpreting the story of Reconstruction for national and international audiences and is senior historical consultant to the Coltrane Group, a non-profit organization in Oklahoma committed to economic development and historic rehabilitation in the thirteen remaining historically black towns in that state. Melissa Stuckey earned her bachelor’s degree from Princeton University and her Ph.D. from Yale University. There’s a common saying where I’m from—“the truth hits different when you’re guilty.” My elders repeated this phrase as both a statement of fact and a warning against covering up future misdeeds. When guilty, they advised us to strengthen our ability to stand fully in our mistakes. They taught us that the same space where one is “hit different” is the space where one learns from their mistakes and can clearly pave a path forward towards truth, justice, and restoration. They encouraged us to recognize these steps as the process of building character. The United States is guilty. And the truth is “hitting different” all across the country. Policing in the United States is rooted in an old belief in which black people and people of color are property and pawns in a capitalist, white supremacist, patriarchal and heteronormative nation-state. For centuries, police inflicted violence on us and our communities when we step out of our place or assert our humanity—when we claim that we are more than what those in power would deem us to be. From slave patrols to the modern-day, militarized police departments, officers are agents of the state imbued with power to capture us and determine our fates. In the past, determining our fates meant tracking down black people fleeing captivity and returning them to white slave owners. It meant invading indigenous lands and seizing their children and sending them to state-owned boarding schools. It meant rounding up and incarcerating Japanese Americans en masse during World War II. Today, it means officers wielding state power on the streets and deciding who lives and who dies and who’s life and communities are ruined. My research shows that for black women, survival includes figuring out how to stay alive and how to protect themselves from the countless ways officers inflict gender-based and sexual violence upon them. In my interviews with black women, they shared stories of being sexually assaulted when pulled over for a minor traffic violation and being told they would receive a ticket unless they complied; of surviving years of child and family domestic abuse from an officer in their home because they felt that no one at the local police department would help them; of being mocked and laughed at when reporting rape or domestic violence; of being afraid in their homes at night after a community police officer who knows where they live sexually harasses them and threatens them with more violence. Many of these black women, like Oluwatoyin Salau a Black Lives Matter protestor who was recently assaulted and killed in Florida, are on the frontlines working to alleviate lethal force and advocate for justice in their communities. Yet, when they speak out on their own behalf, their truths are repeatedly pushed to the margins in conversations on police brutality and considered less urgent matters in discussions on police reform. This is that space in which we must stand. In the past, our anger has coalesced into social movements pushing for visibility and justice. INCITE!, #BlackLivesMatter, #SayHerName, #BlackTransLivesMatter, #SayTheirName are recent iterations from communities and activists attempting to transform our society into a place where everyone is free from violence. For this freedom to be fully manifested, we must include every black person and person of color and contend with every experience of police violence. We must no longer be content with a single story of police brutality. Our outrage must include those on the margins. We must include black people with disabilities. We must include black trans and cis women. We must include black trans men and non-binary people. We must remember the names of Atatiana Jefferson, Tony McDade, Breonna Taylor, Brianna Hill, Pamela Turner, and Regis Korchinski-Paquet alongside George Floyd, Philando Castile, and Eric Garner. We must equally reckon with Shandegreon “Sade” Hill and other victims of Daniel Holtzclaw, a serial rapist who in 2016 was sentenced to 263 years in prison for using his position as a police officer to run background checks on black women and target those with criminal records. We must include the countless other victims, whose names we do not know, of police gender-based and sexual violence. We must include the murders and assaults against black trans women. We can build inclusive and safe communities for everyone by centering those who are too easily forgotten. Black feminists repeatedly urge us to return to the margins, with bell hooks (1990, p. 150) theorizing it as a space that “offers to one the possibility of radical perspective from which to see and create, to imagine alternatives, new worlds.” The margins are where we are hearing calls to abolish and defund policing. The margins are the path forward towards truth, justice, and restoration.

“Mothering, radically defined, is the glad gifting of one’s talents, ideas, intellect, and creativity to the universe without recompense” -- Preface by Loretta Ross in Revolutionary Mothering: Love on the Front Lines [1] “And I want to say to children, tell me what you think and what you see and what you dream so that I may hope to honor you. And I want these things for children, because I want these things for myself, and for all of us, because unless we embody these attitudes and precepts as the governing rules of our love, and of our political commitment to survive, we will love in vain, and we will certainly not survive.” -- “The Creative Spirit: Children’s Literature” by June Jordan in Revolutionary Mothering: Love on the Front Lines [1] As we prepare for Mother’s Day on May 10, 2020, we should take a moment to celebrate the mothering labors we have received and given, to acknowledge our ancestors (biological, chosen, spiritual, and intellectual), and to reflect on the networks of care in which we are enmeshed. This blog post was written by three black women academics and mothers - two anthropologists and one sociologist, two junior faculty and one tenured department chair, two married moms and one single mom. Recently, Caroline Kitchener interviewed two of us for an article in The Lilly about women academics submitting fewer journal articles during the pandemic. As scholars and mothers, we were inspired to write this blog to more fully share our stories. It is our hope that by being transparent about these struggles, and sharing our concerns and points of clarity, we can build community and remind readers who are sheltering in place that they aren’t alone in their struggles. We also hope to illuminate the connective tissue that connects our shared kinwork as mothers. *** Erica L. Williams The impact of the pandemic on my academic work life has caused me to reflect on Cite Black Women Guiding Principle #5 - “Give Black Women the Space and Time to Breathe.” We need uninterrupted time to sit, think, read, and write, especially when we are in the generative and creative phase of writing new work. But that is exactly what is in short supply as work-from-home + homeschooling academic mamas during this pandemic: the imagined “work/life balance” of the academy is dissipating for black mothers during this crisis. I occupy a privileged position as a tenured Associate Professor and department chair who lives in a house my partner and I own. We live on a tree-lined street in Atlanta with a wooded trail at the end of our street and in close proximity to grocery stores. I have a partner who is also working from home and who is committed to an equitable division of labor in our household. Since sheltering-in-place began, , we have gone back to a strategy that we used when our son was an infant - split shifts. My husband takes responsibility for our son in the mornings until about 1pm and then I take over until about 6pm. That way we each get a few hours each day to focus on our work. “Work,” no longer means writing for me though. Now, my work time mostly consists of carrying on the business of the College and my department - advising students, teaching classes, grading, Zoom committee meetings, etc. In the afternoons after my morning “work shift”, I switch gears to immerse myself in homeschooling activities with my son. We do music and movement, storytime, phonics lessons, science and math. We also do worksheets that my husband and I print out from the internet, so that he can practice writing letters and numbers, identifying sight words, counting and simple math. Sometimes we also take it easy and do puzzles, play Scrabble or Jenga, go for nature walks on the trail near our house, or cook dinner. We want to ensure that he will be ready to enter kindergarten next year. If teaching and service were the only expectations placed on me as a scholar, perhaps my current extra demands wouldn’t be so bad. However, as scholars, we are expected to produce knowledge and participate in an intellectual community. I have two book projects in progress that I have not touched since the pandemic began. “In the before” I used to have a weekly writing group at a cafe with two other academic mamas. We would gather right after dropping off our kids at school and sit together for 2-3 hours. One of them was doing a daily writing challenge with the goal of writing at least 30 mins a day during the semester. I decided to join her, so I made a cute little Excel spreadsheet where I would log my writing times. I didn’t meet my goal of writing every day before everything changed, but I would at least get in a few days a week. Now, I have to compress a full-time job into half a work-day and a few stolen hours on weekends, evenings, and early mornings. Instead of texting for writing accountability, my writing group texts just to see if we are making it through the day. My cute little Excel spreadsheet, where I had planned out all of my writing projects, is now collecting dust. I no longer have time to squeeze my academic projects into the day. That’s just it: What is particularly challenging for us as academic moms right now is that many of the strategies for success that we learned in graduate school or on the tenure track, such as having firm boundaries around our time, have been completely upended by this crisis. Whitney Pirtle I agree with Erica. My privilege right now is undeniable. I have retained my job and my paycheck, as has my husband. He, I, and our two children (9 and 4), live in a home we own. My family is healthy, our neighborhood remains uncrowded, our cupboards stocked. Shelter-in-place is doable. As someone who was raised by a single mother and grew up below the poverty line in a subsidized townhome with three siblings, I know acutely how differently this pandemic might feel to me if I did not have the job security, autonomy, and privilege of being an academic on the tenure track. If this hit 15 years ago, I know I would witness my mother creatively try to stretch the stimulus and unemployment payments as far as she could and rely on additional donations to sustain us. We wouldn’t have a computer to do the distance education programs, furthering educational gaps already shaped by our social class. Having to manage our emotions on her own with no breaks, might have broken all of us. Every single time I find myself gasping for air as I attempt to balance teaching, writing, service, homeschooling, pre-k, and household chores, and existential worry about the world, I think about my privilege. I tell myself that I am ok, that the kids will be ok; I exhale. I exhale. But the stress I feel is real. Despite the protections that I have and that I give gratitude to every day, it is true that I am struggling. I cannot do it all. I have never claimed to do it all, and yet, I am put in a position where I feel I have to do it all. I am an advanced assistant professor and sometimes feel I can audibly hear the clock ticking in my head. I have taken the tenure extension but my dormant book project- the thing that my last review said will hurl me over to promotion- haunts me. I average two zoom meetings a day, responding to my students, research teams, phd candidates, department needs, student org advising. I work every day, even on the weekend which was never my thing, but my time to write is minimal nonetheless. Schedules are jokes. None of us seem to have bedtime anymore. My kids are struggling too. My sons are crazy active, both already in sports, are often now just stir crazy. The zoom meetings, classes, and webinars do little for them and their want of social interaction. My short fuse means I fuss way more than I’d like. They are not getting a rigid curriculum right now because I cannot sustain it. My husband, a school principal, is tasked with managing school lunches, distance learning, teacher, student, and parent concerns- restricting the time he has to instruct our kids too. At least youtube makes them laugh. When I see that journal submissions are down from women authors, I laugh and think “of course they are.” I know how the pandemic, work-from-home, and distance learning for k-12, takes a toll on all that I have... even though I have so much. I also know that parents doing it solo are taking additional tolls, as are those in contingent positions. I also know that the gender aspect extends to women who don’t have children, given the ways we are socialized and the structures in place that make us caretakers of families and communities. I know that this impacts Black women for the ways we are asked to mother, as mothers to children or not. Asking us to do it all is not sustainable, nor is it equitable. I try to remember my mantra of “just be good” as I inhale and exhale. For me, being good enough is a radical approach to role overload and a survival strategy, especially for mothering in the academy while Black. In that approach, I focus on what is most important and shape schedules around those things. And then, I aim to be good enough at them. This is because if I try to excel at one thing I typically let the ball drop on another; Lynn Bolles tells us being multitask oriented is a key to survival for Black women in the academy.[3] My covid-clarity is to be good to myself, my family and children, and my immediate job tasks. And to always, remember to breathe. These tasks are more easily achieved, however, when we are given, through policies and resources, more time and space to breathe. Todne Thomas It’s a Monday afternoon. My son and I gear up for the next activity in our makeshift homeschool. It has increasingly become a blend of school-provided worksheets, community-based learning Zooms, and our own creation of assignments that speak to some of the questions he has about the world. One day, my son wanted to know what I do for research, and if he could do it, too. I talked about ethnography and interviewing. He decided that he wanted to interview me for school. I asked him to prepare at least five, open-ended questions for our interview. After my prompting to begin the interview with a descriptor, the interview opened with his enthusiastic introduction, “I’m asking her about things she does and things she is.” As adorable as that tag was, youngblood didn’t hold back any punches. I paused, inhaled, and proceeded to answer his questions. I include a transcribed excerpt from our interview below. Kid: How hard is it being a Mom? Mamademic: () Whew! How hard () that’s a really good question. Umm () how hard is it, how hard is it? It is definitely the hardest thing I’ve ever done. But, it’s also very rewarding. Umm, it just depends. You know some days are easy days and Kid: Some days are harder. Mostly hard. Mamademic: No. They’re not mostly hard. They’re mostly in the middle, but it definitely is () involves a lot of sacrifice. Kid: Do you have fun being a Mom? Mamademic: I do. I do have fun being a Mom. I’m lucky because I have a very fun kid who’s very funny. Kid: Why is that? Mamademic: I have a son who’s very funny who likes to make lots of jokes. Kid: By the way that’s me. Mamademic: (laughing) There are things we do I really like. I like dance parties. Sometimes you ask me questions that are really funny. I really like comic book Marvel movie () um () culture you know what I mean? Kid: We’re Marvel people. A bit of DC, but mostly Marvel. Mamademic: We have stuff we do that I really like doing, and I wouldn’t want to do with anybody else. I was honest in my responses. It is a challenging and beautiful life trying to balance the labors of mothering and scholarship. There is the joy of having a son who wants to know you better. There is laughter. Yet, perhaps some of the readers noticed the pauses (), the umms, and repetitions that permeated my responses. There are good days, bad days, and worse days. The days in the middle are often attended by feelings that I am failing at one, if not, both aspects of the work-life divide. The rough days may fall into the realm of the ellipsis waiting for the readers who know, who have the context to understand, who can fill in the spaces between the words. As a single mother and junior faculty member, it has always been difficult to make sense of the irreconcilable and even warring spheres of work and life. The work context precipitated by the Covid-19 pandemic has aggravated this tug-of-war. Without access to my office space, the library, and most importantly face-to-face interactions with research collaborators, what counts as “work” is its own work-in-progress. My unexpected transition from a sabbatical research year to working from home while simultaneously educating my child has also required us both to revise our understandings of “school.” These new re-definitions take place amidst a context in which the gender divide in research productivity is heightened.[1] Most days still end in the middle, with good and bad days peppered in. Nonetheless, the crossroads of my aching intersections also hold insights. I list three “Covid Clarities” that have helped me traverse my insecurities about sustaining work productivity and maintaining my increased educational and caregiving responsibilities. Covid Clarity #1: Sometimes we can’t count on intelligibility. If I had a dollar for every time someone asked me, “I don’t know how you do that,” in reference to the work-life hustle, I would have…well a lot of dollars. There are times when it is necessary to outline the inequitable workloads we carry as women. There are also instances when doing this translational work ad infinitum can become too taxing. As I often teach in my classes on religion and race in the United States, “Privilege is blindness.” Some people can’t see, and some people are invested in not seeing because of the discomfort that a new world view might instigate. You know what load you carry, and if you’re fortunate you have people who understand that load. Too much translation of these inequities to people who may not understand in this moment can drain the cognitive and temporal resources we need to survive, make order, make meaning, and provide care in this unprecedented moment. Covid Clarity #2: Intellectual production is communal. Though the dominant model of intellectual production tends to award single-authored manuscripts, outstanding ideas are instigated, nurtured, and co-produced in community contexts. This year, I benefited from dynamic conversations with the 2019-2020 class of fellows at the Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study and was challenged to think of art, gender, labor, embodiment, and visuality in ways that will undoubtedly shape my work for years to come. One of my fondest memories was coming together to knit a blanket to give a new mother and daughter in our fellowship class. There was laughter and learning and mistakes and food and survivorship and mentorship. We made ourselves as we made a thing. Witnessing fellow womxn-of-color anthropologists share their gifts as dance teachers, yoga instructors, and artists via online courses, creating emergent mutual aid networks by sharing information, resources, and experiences, and writing to, in, and from this moment has never made me more honored to be an anthropologist. Moreover, emergent thoughts and ideas about how fieldwork is being changed by a new state of immobility[4] along with ongoing work of scholars like Aimee Villareal and David F. Garcia (2019),[5] who in their Anthropology News article have argued for creating an “anthropology of anthropolocura” that is “political, decolonial, and intersectional,” makes me genuinely excited about the kinds of anthropology we can conceive and give birth to in this moment. Kinds that are kinder to our social locations and intersections, where we can write with and from our mother places. Covid Clarity # 3: We need new reference points. Comparison tends to be a one-way ticket to unhappiness. It is important to have role models, and archetypes whose accomplishments can inspire. It is important to share strategies and to have mentors for the different parts of your life. Nonetheless, solely using paragons of productivity who share few to none of your caregiving responsibilities or dimensions of lived experience may leave you lost as last year’s Easter’s egg. We need new models of well-rounded productivity and gentle networks of wellness and accountability for this moment. We need people who will help us breathe while inhabiting the life side of the work-life paradigm, because a lot of life (a lot of everything) is happening, now, fast, inside and outside of our doors. And, to use the words of Audre Lorde to depict what my colleagues are demonstrating in this moment, “We are the ones we’ve been waiting for.” *** As black women, mothers and academics, we can look to ourselves and foremothers, othermothers, co-madres, and colleagues as sources of inspiration and accountability. We can also create networks of aid, recognition, and scholastic production that makes use of collaborative models of writing (like this blog post). But most importantly, we can take a moment to play, do those puzzles with the young ones, laugh, pause and make space for Marvel movies. Then, on the bad days, we can breathe, and inhabit our versions of “good enough.” [1] Revolutionary Mothering: Love on the Front Lines. 2016. Edited by Alexis Pauline Gumbs, China Martens, and Mai’a Williams. PM Press. [2]Caroline Kitchener. April 24. TheLily.com https://www.thelily.com/women-academics-seem-to-be-submitting-fewer-papers-during-coronavirus-never-seen-anything-like-it-says-one-editor/?fbclid=IwAR1GUwBPiUh9MiT92jDNtIwlbgcKcQIb3QGHvTBIq38fNvm7FZtCUYid3tQ [3] Bolles, Lynn. 2013. “Telling the Story Straight: Black Feminist Intellectual Thought in Antropology” Transforming Anthropology. 21(7):57-71. [4]https://allegralaboratory.net/ethnography-at-an-impasse-fieldwork-reflections-during-a-pandemic/ [5] https://anthrosource.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/AN.920 Whitney Pirtle is an Assistant Professor of Sociology and affiliated faculty in Critical Race and Ethnic Studies and Public Health at the University of California Merced. Her areas of expertise are in race and nation, racial/ethnic health disparities and equity, Black feminist sociology, and mixed methodologies. She has also written about being a mother in the academy for Chronicle and Inside Higher Ed.

Todne Thomas is an anthropologist who specializes in religion, race, and kinship, is an assistant professor of African American religions at Harvard Divinity School and a Suzanne Young Murray Assistant Professor at Radcliffe. Erica L. Williams is Associate Professor and Department Chair of the Sociology and Anthropology department at Spelman College. She has a Ph.D. and M.A. in Anthropology from Stanford University. Her books include Sex Tourism in Bahia: Ambiguous Entanglements (2013), and a co-edited volume,The Second Generation of African American Pioneers in Anthropology (2018).  April 25, 2011: ok, I think I get it now: when you feel like you absolutely have no time for anything else, that's when making time for self-care is the most important. I'm feeling so good and clear and productive after my morning workout on my 2 lectures day. I enjoy looking at the memories that pop up during my morning scroll on my Facebook timeline. When this little gem popped up a few days ago, I immediately shared it because it seems all the more relevant now. My 4 year old son has been out of school since Friday, March 13, so I have now been a work from home/homeschooling mama for six weeks. This time has made me reflect a lot more on the self-care practices that are life-sustaining for me. Another flashback: on November 5, 2012 I published “A Black Academic Woman’s Self-Care Manifesto” on The Feminist Wire.[1]At the time, I was on my 4thyear of the tenure-track at Spelman College. I was unmarried with no small children. I prided myself on being able to set firm boundaries around my time: “For me, self-care quite simply means setting boundaries on how and when I work. I refuse to run myself into the ground by working around the clock with no time for rest and relaxation. The academy tends to privilege a lack of sleep, workaholic tendencies, and scholarly productivity at the expense of everything else. I refuse to sacrifice my nights and (whole) weekends for work. Evenings are reserved for exercise, family time, home-cooked meals, and general “down time,” and I will not be made to feel guilty about that.” Oh, how times have changed. Now I am a tenured Associate Professor of Anthropology and Chair of the Sociology and Anthropology Department. Now I am a whole married woman with a 17 year old stepdaughter (who lives with us full-time as her mother is in another country) and a 4 year old son. Now we are living in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic, which has caused changes to our lives that we have never seen before, nor could we have ever anticipated. Now I have to figure out how to do my full-time job in a half a day so that I can spend the other half of the day homeschooling my 4 year old. There is no boundary between work and home. Work life bleeds into home life bleeds into work life… Many of you may be managing similar struggles, trying to figure out a healthy routine in these unprecedented circumstances. In times like these, being committed to self-care becomes even more important. As someone who suffers from anxiety and a family history of diabetes, I feel an even stronger need to take physical exercise and stress relief very seriously. Here are some things I’ve been doing:

ETHNOGRAPHIES

FICTION

I’ve been taking full advantage of virtual offerings to get workouts in. “In the before” I was never big on home workouts. I loved doing exercise classes – I belonged to a kickboxing gym, and had a Classpass membership that would allow me to try out different fitness classes in studios around metro Atlanta. However, luckily I had begun building up my home workout equipment “in the before” I got a yoga mat, cushion, blocks, and strap; got 5, 10, and 15lb dumbbells, and resistance bands. My kickboxing gym has my favorite coaches posting videos, so sometimes I do that as my workout. There is a nice (not crowded), wooded trail near my house, and my son and I go for walks on it a few times a week. An Afro-Colombian dance and Zumba teacher has been teaching dance/Zumba classes 3x a week on Twitch for free, and I have joined into her class as often as possible. Also, Classpass has expanded to offering members an opportunity to sign up for livestream classes all around the world – and some are for 0 credits! I only pay $12 a month for a certain number of credits for classes, and if classes are in the low range then I can squeeze in quite a few per month. I have done yoga, HIIT, and meditation classes via Classpass livestream offerings. They also have workout videos posted. I also have a once-weekly workout via Zoom with a friend who lives in Chicago, and join into an NYC friend’s workout class two mornings a week. After a few weeks, getting my daily dose of exercise has finally become a habit. It makes me feel good, strong, refreshed. Sometimes I’ll do it at 8am or 6:30pm, depending on what I have going on for the day.

What ideas do you have about self-care during the pandemic? What works for you? [1]https://thefeministwire.com/2012/11/a-black-academic-womans-self-care-manifesto/ Dr. Erica L. Williams is Associate Professor and Chair of Sociology and Anthropology at Spelman College. She is also a member of the Cite Black Women Collective. Her full bio is available on our Collective members' page on this site.

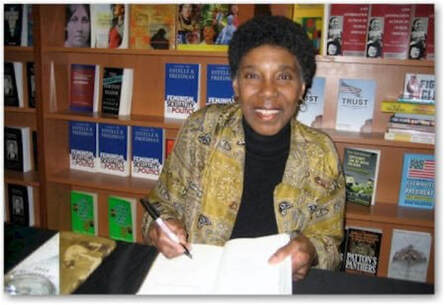

On March 19th, the metropolitan region of Rio de Janeiro announced its first death from the COVID-19. She was a 63-year-old hypertensive and diabetic domestic worker who was taking care of her employer, a 62-year-old woman who lives in the upscale Leblon neighborhood of Rio de Janeiro. The employer had just arrived from Italy—one of the countries hardest hit by the virus so far—and did not advise her domestic worker that she was sick. Although the woman was in isolation after her trip (“selective confinement”), she still relied on her domestic worker to come in, clean and take care of her—an aspect of social distancing that few are discussing. As the Coronavirus pandemic paralyzes the world, poor Black women in Latin America are particularly vulnerable to the disease and no one seems to care. At first, it seemed as if Coronavirus was primarily impacting the white, the rich, and the elite. Yet, over the past week, stories out of Brazil reveal the vulnerability of those who take care of those who are infected (with our without symptoms) beyond hospitals. In Brazil, Black women disproportionately work as domestic workers, and domestic workers are particularly vulnerable, and invisible in our discussions of the dangers of the disease. Several recent cases across Brazil reveal the risk that domestic workers face. A businessman from Rio de Janeiro received the news from his doctor that his test was positive for CODVID-19 by telephone. The man infected was in a steakhouse, surrounded by friends and his wife, who was later infected as well. Although the two went into isolation, their maid-- the only person who lives with the couple, and who now works in "gloves and masks"-- did not count as someone that should be put in isolation. In Bahia, my home state in Brazil, this pattern repeats itself. The first case of a person infected was in the city of Feira de Santana. The first person infected, a 34-year-old womanreturned to Brazil from Italy carrying the virus with her. She was tested for the virus in a private hospital. However, despite orders to remain "in isolation", and monitoring by the state health secretary, the woman’s42-year-old domestic workeralso became infected. The domestic worker’s 68-year-old mother became the third infected. Historically, Black women have been the hands that clean up after the world. However, recently two trends have made this work more precarious. On the one hand, neoliberalism has continued to devalue domestic, leading to less stability and continued low pay. On the other hand, austerity measures have meant that funding for cleaning at the state level (in schools, universities, public places) has been cut drastically in places like Brazil, putting us all at risk. There is a direct connection between austerity, the risk we face with public hygiene, a reduction in public services like funding for university education, and the vulnerability of domestic workers. Here in Brazil, our university campuses get dirtier by the day. In 2016, the federal government cut public spending and investment in health care and education drastically. One of the first signs of this cut was the outsourcing of cleaning staff. Composed mostly of Black workers, government-contracted cleaning teams that were not fired became overloaded by extra shifts and extra work. Now, as the world waits for a Coronavirus vaccine, personal hygiene and aggressive cleaning of public spaces are the most effective way to fight the proliferation of the virus. Most often this means that our health and our very lives are in the hands of the domestic workers who clean our public and private spaces—and across the Americas that frequently means Black women. Last Saturday I was on the campus of the Federal University of Bahia and one of the bathrooms was spotless. A Black worker, alone, almost compulsively cleaning the men's and women's bathrooms at the same time. Yet while this one woman was working above and beyond to try to keep us safe, at my campus outside of the city limits, the bathrooms remain dirty because the workers who once cleaned them have been laid off. My university, the Federal University of Recôncavo da Bahia, has suffered from recent federal government cuts in education. Most of the classrooms smell like mold and have no ventilation. Oftentimes we do not have running water or hand sanitizer. Undervaluing domestic work has a direct impact on our health. Cleanliness has a race, gender and class. The other day I was watching a popular news program. One infected and isolated interviewee said, "The worst thing about quarantine is having to cook your own food." Another claimed that she had never imagined herself infected with a virus like this. In other words, many of the privileged elite who contract the virus believe that getting sick from epidemics is a thing of the poor. It is as if it were an “uppity virus" , that blindly disrespects social hierarchies, throwing everything upside down. What did the privileged expect from this pandemic? They expected COVID-19 to be like dengue fever, zika and chicungunha-- “poor people’s” diseases that afflict spaces neglected by the state (these diseases are linked to basic sanitation issues like access to clean, running water). When poor and Black people were the disproportionate victims of rabid disease, no one seemed to care. Now that the white elite are particularly in focus, the sense of social responsibility has shifted, yet Black women still remain particularly at risk. Domestic workers depend on Brazil’s university health care, use public transportation, live with their families daily, and cook their own food. Many of them work informally and do not receive sick leave or qualify for unemployment should they have to stay at home. What happens when their kids' schools close? Are they allowed to stay at home? If isolation means that infected people are distant from other people, why don't they count? It is time for us to consider the race, gender, class dimensions of this global pandemic. * Credits: A mão da limpeza (The Hand of Cleanliness) is a composition by Gilberto Gil and is on the album A raça humana - The human race, which by the way is very relevant for the moment and we should listen all these days that we are at home… for those who can afford to work From home. Luciana Brito is an historian, member of the Black Women's Network of Bahia, and identifies herself as a black intellectual and working-class feminist. She is a professor in the Department of History at the Federal University of Recôncavo da Bahia-Brazil, specializing in the history of slavery and abolition in Brazil and the United States. She is also interested in the areas of race, gender and class in the Americas. She is the author of several articles and the book Temores da África, which will soon be published in English. Instagram: @lucianabritohistoria  On Friday, March 6th, I had the pleasure of interviewing two prolific scholars in the field, Drs. Daina Ramey Berry and Kali Nicole Gross on their most recent coauthored book, A Black Women’s History of the United States(Beacon Press, 2020). As a history graduate student, I am always thinking about the gaps in the literature including the underexplored topics, so when I asked Drs. Berry and Gross if their work was picking up on themes that they thought were missing from the previous generation of historians, their response problematized my original question. Instead of approaching the field of Black Women’s History through the lens of critique, they informed me that they were interested in showcasing how the scholarship has evolved over the last two decades. It was not that pioneering historians like Paula Giddings, Deborah Gray White, Darlene Clark Hine, Sharon Harley, and Evelyn Brooks Higginbotham lacked analytical substance. Rather, the newer generation of scholars are asking different questions and developing innovative methods to recover black women’s voices in archives bent on erasing us. Drs. Berry and Gross remind us that we stand on the shoulders of black women historians who labored before us, and as we expand the field, it is necessary to acknowledge and cite their foundational works. A Black Women’s History of the United States traces our history in the Americas from before slavery to our central role as the backbone of contemporary movements against persisting injustices. In writing such an expansive survey of Black women’s history, Drs. Berry and Gross discussed the process of collaborative work. They highlighted the manuscript workshop with their “Sister Scholars” in the field, and how it was through consulting with other black women historians that they received feedback and suggestions on themes and approaches for the book. For example, from the Sister Scholars workshop, Drs. Berry and Gross got the idea to start each chapter with a narrative of a black woman’s experience to correspond with a new periodization. In these anecdotes, we learn about figures that disrupts traditional histories of the U.S. like Isabel de Olvera, a free woman of African descent, who migrated to the U.S. before 1619. And even others, such as Aurelia Shines, a black woman who challenged Jim Crow’s segregation laws by refusing to give up her seat in 1948, seven years before the infamous Rosa Park’s protest in Montgomery. While their work foregrounds the ways black women navigated the double oppression of race and gender, Drs. Berry and Gross’ analysis refuses to place our history as purely oppositional or only existing to combat white supremacy. Instead, A Black Women’s History of the United States accounts for both black women’s resistance and liberation struggles, and their leisure activities through travel, art, and the erotic. Drs. Berry and Gross helps us rethink black women’s intellectual labor as a collective, which reframes our professional pursuits. As we move in a space like the academy that is designed to monopolize and capitalize on our movement and labor, Drs. Berry and Gross reminds us of the important role community play in surviving and confronting such exploitation. It is in the collective that we liberate ourselves from the individualistic, “clout-chasing,” performative aspects of academia. This collectivity prompts us to continue organizing conferences, workshopping our research, and building professional and mentorship relationships. I am grateful for the opportunity to have had a conversation with Drs. Berry and Gross about their new book, and I am sure this text will ignite a new generation of scholars to continue to do the work. Tiana Wilson is a third-year doctoral student in the Department of History with a portfolio in Women and Gender Studies, here at UT-Austin. Her broader research interests include: Black Women’s Internationalism, Black Women’s Intellectual History, Women of Color Organizing, and Third World Feminism. More specifically, her dissertation explores women of color feminist movements in the U.S. from the 1960s to the present. At UT, she is the Graduate Research Assistant for the Institute for Historical Studies, coordinator of the New Work in Progress Series, and a research fellow for the Center for the Study of Race and Democracy. Check out Tiana Wilson's interview with Profs. Daina Ramey Berry and Kali Nicole Gross for the Cite Black Women Podcast.

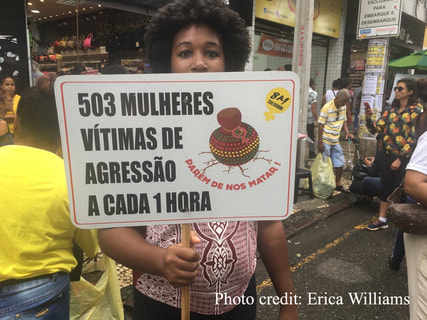

This past July I was in Salvador to do research on black women’s activism during the month of Julho das Pretas(July of Black Women), which Odara – Institute of the Black Woman started seven years ago. Julho das Pretas was initially launched as a way to bring attention to July 25 – the Dia Internacional da Mulher Negra da America Latina e o Caribe (International Day of the Black Latin American and Caribbean Woman). July 25th has been celebrated since 1992, when a group of women organized the first Encontro de Mulheres Negras Latinas e Caribenhas in Santo Domingo, the Dominican Republic, and created the Rede de Mulheres Afro-Latino-americanas e Afro-Caribenhas.[1]Thus,Julho das Pretaswas seen as a way to celebrate black women and raise awareness about the issues facing black women for the entire month of July. Julho das Pretas has now spread all over Brazil. On July 25, 2019, black women gathered in major cities all over Brazil for the Marcha das Mulheres Negras. I was able to attend the Marcha das Mulheres Negrasin Salvador, Bahia, which had the theme: Mulheres Negras por um Nordeste Livre Do Racismo, da Violencia, e pelo Bem Viver(Black Women for Northeast Free of Racism, Violence and for Good Living). On the Facebook page for the march, the organizers wrote, “the march will bring together plural black women, to shout out against racism, violence, femicide, LGBTphobia, maternal mortality, obstetric violence, the genocide of black youth, religious and environmental racism, against welfare reform, cuts in education and all forms of fascist and white supremacist oppression and ignorance in force in national politics.”[2] We gathered in Piedade plaza starting at 1pm.Staff members from Odara kicked off the march by welcoming everyone to the march, and inviting people to share their thoughts with the crowd on the open mic. Milca Martins, Secretary of Sindoméstica, the union of domestic workers, spoke out about the urgency of black women saying NO to all the various forms of violence that they suffer. Hailing from the peripheral neighborhood of Mata Escura, she encouraged everyone present to form women’s groups in their communities, and to work with women from periphery. She even brought women from Mata Escura with her to the march, for whom it was their first time participating in the march. Martins pointed out that the first to be hit by the recent controversial welfare and retirement reforms of are black women. She got emotional when speaking about the unjust situation in which black women domestic workers often find themselves in – “the system is killing our kids and they ask, ‘where’s you mom?’ And we are working taking care of white children and don’t have anywhere to leave our children!” After Milca Martins’ speech, Odara staff members gave rousing speeches with lots of neighborhood shout outs. There were multitudes of black women of all ages gathered in the plaza. A capoeira group called Sonho do Zumbi performed, with mostly women capoeiristas jogando (playing). People went up and read poetry. The sisters of the Irmandade de Boa Morteopened the march as a symbolic act of reverence to what Afro-Brazilians call “ancestralidade.” The literal translation of the word is ancestry, but it is much more than family or genetics – it has to do with African cultural heritage, practices, aesthetics, and religiosity that has fortified Afro-Brazilians and given them the strength and fortitude to resist enslavement, colonization, and continued racism and oppression in Brazil. Ironically, while the Odara staff were asking for people to clear a path to allow the elder black women from Boa Morteto open the march, the media swarmed in front of the irmãs, with journalists sticking microphones in their faces and trying to get interviews with their video cameras. It was a tense and awkward moment in which the media clearly was acting in their own interest, but ironically, holding up the progress of the march! When the march did get under way, it was marvelous. The mic was open the entire time as we walked down to Cruz Caída in Pelourinho. Two black trans women spoke out about how transwomen and travestisare also a part of the black women’s movement, and how they are especially vulnerable because they are often locked out of the job industry due to their gender identity. At some point, it began raining – first a sprinkle, and then it poured. The crowd dispersed a bit around Praça da Sé, but the rain did not dissipate the energy of the march. Once the rain passed, the crowd regathered and continued onward. That felt symbolic to me, somehow. Much like the struggles that black women face, we protect ourselves from the rain, but then regroup, find strength and solidarity amongst our sisters, and continue on our way. In this Instagram post advertising the March, it says “For a Bahia free of Femicide” and shows women holding signs about the high rates of violence against women. The signs claim that there are 5 beatings of women every 2 minutes and 1 woman murdered every hour two hours. Notably, a disproportionate amount of victims of this type of violence in Brazil are black women. On November 27, the news of yet another femicide of a young black woman with a promising future rocked the black feminist activist community of Salvador. Elitânia Souza da Hora was a 25 year old student in Cachoeira, Bahia, and a quilombola leader who was murdered by her ex-boyfriend. The tragic irony is that she was preparing to defend her undergraduate thesis on the topic of femicide, and then she became a victim of it. In the spirit of citing black women in transnational contexts, I want to share my translation of the Nota de Repúdio from the Forum Marielles de Mulheres Negras de Salvador. FROM MARIELLE FRANCO TO ELITÂNIA SOUZA DA HORA: WHO CARES ABOUT THE LIVES OF BLACK WOMEN? December 1, 2019 English Translation By Erica Lorraine Williams On the afternoon of November 22 of this year, a Babalorixá from the city of Santo Antonio de Jesus, in the Recôncavo of Bahia, sent me a Whatsapp message distressed. He said he was going to do an activity in his religious house on December 1, and invited me to a roundtable discussion on the topic of “Femicide,” which he had chosen at the behest of a deity. The gods were worried about the violent occurrences that had been affected women of the city. On November 27, we were horrified by the news that Elitânia Souza da Hora was cruelly murdered when she left her classes at the Federal University of the Recôncavo of Bahia (UFRB), in the city of Cachoeira, Bahia. A brilliant young black woman, she was a quilombola leader who worked for an NGO of the valorization of the culture of the Recôncavo Baiano. She had her whole future ahead of her. She was going to graduate with a degree in Social Services and she was part of CASSMAF, the Academic Center of Social Services Marielle Franco. Like many women in Brasil, Elitânia da Hora found herself trapped in an abusive relationship with a man who wouldn’t leave her in peace. A victim of domestic violence, she had already reported the case to the police station, and she even had a protective order against the ex. She was a woman with a big smile, always nice and kind, with strong opinions and dreams of a successful professional life. On the other hand, the brutal assassination of Marielle Franco last year also shocked us and, as the case has unfolded, the way the Brazilian system of justice has handled this heinous crime continues to frighten us. The high rates of femicide in Brasil are also scary particularly when we analyze them from a racial dimension. According to data from the Ministry of Health compiled by the Atlas of Violence, launched by the Institute of Applied Economic Research (Ipea) and by the Brazilian Forum of Public Security (FBSP), for example, 4,936 murders of women were registered in 2017. That is an average of 13 homicides per day, the largest number in a decade! According to information from the Map of Violence, in Brazil between 2003 and 2013 the number of femicides of black women jumped from 1,864, in 2003 to 2,875 in 2013. In contrast, there was a decrease of 9.8% in crimes involving white women, which fell from 1,747 to 1,576 between the years. The death of Marielle Franco added to this statistic. And it was from the idea of honoring the council woman from Rio de Janeiro, that the Fórum Marielle of Salvador-Bahia was created, with the objective of encouraging the candidacies of black women in spaces of power, because we recognize that such women find themselves under-represented in these spaces, even as they make up the majority of the Bahian population. Since its creation on March 14, 2019, we have gathered to discuss various topics of interest of black women and we have perceived the strength and potency of the diverse organizations of black women that make up the Forum. However, femicide remains untouchable for us black women, as a constant threat to the lives of these women and to their well-being. The death of Marielle Franco also made this complaint, therefore our goals as a Forum that brings together dozens of organizations of black Bahian women is also to fight against this necropolitics adopted by the Brazilian state, that has a tragic impact on the well-being of black women, we want to denounce and unite in diverse fronts of confronting this extermination. Many organizations of women have long been engaged in this fight against the genocide of black people and against femicide. In Bahia, we have for example the Campaign Parem de Nos Matar(Stop Killing Us), organized by the Bahian Network of Black Women o, the Community Forum to Combat Violence which develops several actions and a vigil every month in Lapa station in Salvador, collectives like Mahin – Organization of Black Women, that carries out actions with women in situations of violence in peripheral neighborhoods, and Odara – Institute of the Black Women, that also has a campaign on this theme, among other organizations and collectives across the state of Bahia. The state government, in its turn, also possesses secretaries and other organs of the justice system that deal with this issue, but they seem dead to us, at least with regard to the deaths of black women, since in this group femicide has increased, demonstrating that the policies appear to be effective for white women, but not for black and brown women. The state can’t even guarantee what the law advocates, for in the case of the Rio de Janeiro Council Woman Marielle Franco and of Elitânia Souza da Hora, the young Social Services student at UFRB, the state failed and wasn’t able to offer the protection that they needed, not even through complaints nor in the guarantee of the protective order, nothing prevented the monstrous murderer from taking the life of Elitânia, a young black quilombola woman, active in the student movement and in defense of affirmative action policies. We of the Fórum Marielle denounce this and we put ourselves on the alert in the face of so much neglect, and we demand answers of the appropriate instances, we will speak up, denounce, and demand our rights, so that all black women may live their lives without being interrupted! FORUM MARIELLES DE MULHERES NEGRAS DE SALVADOR [1]http://www.palmares.gov.br/?p=54714 [2]A marcha reunirá mulheres negras plurais, para gritar contra o racismo, a violência, o feminicídio, a LGBTfobia, a mortalidade materna, a violência obstétrica, o extermínio da juventude negra, o racismo religioso e ambiental, contra a reforma da previdência, os cortes na educação e todas as formas de opressão e ignorância fascista brancomachocêntrica em vigor na política nacional.  Dr. Erica L. Williams is Associate Professor and Chair of Sociology and Anthropology at Spelman College. She is also a member of the Cite Black Women Collective. Her full bio is available on our Collective members' page on this site.  Rosamond S. King Rosamond S. King Somewhere, sometime, in every work of fiction written by Paule Marshall, a black woman laughs. But the laughter is not always the same; there are multitudes of knowledge, skill, and feeling in her different types of laughter. There is laughter that derides others, of self-loathing, of survival, and of freedom. Each novella in Marshall’s book Soul Clap Hands and Sing has a male protagonist. And yet each piece still manages to be about black women and how their appearance alters the way men feel about themselves. In “Brooklyn,” a white male professor consistently refers to the only black woman in his literature class as “girl” in his fantasies. At first, she is intimidated by him, and frightened when he solicits her, but later she approaches him to affirm her own sense of self – and “her sudden laugh [was] an infinitely cruel sound in the warm night.” This black woman’s laughter is mean and doesn’t fully endear us to her, but Marshall makes it clear that it took many years and a great deal of loneliness and pain for her to earn that laugh. Some of the laughter in The Chosen Place, the Timeless People – a novel which showcases Marshall’s talent for writing about visceral emotion – is also painful. Merle, a black Caribbean woman, is deeply haunted by her past, and she holds her ex-lover, a white Englishwoman, responsible for much of her misery. Yet Merle manages to empathize with the white wife of a man she has an affair with, until the woman tries to pay Merle to leave. The bribe is so close to how that other white woman treated her that after the offer, Merle’s “head went back and the earsplitting laugh erupted once again. And this time it was more a laugh and less the anguished scream that had sought to rid her of the dead weight. She might have been delivered.” Merle’s own laughter delivers her; she finds within herself the route from pain and guilt towards freedom and self-acceptance. In Marshall’s fiction, black women’s laughter is hardly ever at something funny. Instead, it’s a response to the absurdity of life, and especially of racism and poverty. It’s what in some places we call laugh for not to cry. The novella Reena describes this kind of laughter. As the title character and an old friend mourn being aging black women who are both alone and lonely, “again our laughter – that loud, searing burst which we used to cauterize our hurt mounted into the unaccepting silence of the room.” Not all of the laughter in Marshall’s work is painful. Despite her mother’s warnings, Selina, protagonist of Marshall’s first and probably most-taught novel, Brown Girl, Brownstones, seeks out Suggie – a single, “loose” woman – for information and advice about sex. Suggie happily complies, and at the end of the chapter (in what some describe as a homoerotic scene), "Together, laughing, their arms circling each other’s waists, they crossed the room and opened the door. A wide bar of light from the hall made a path for them, and the rich colors of their laughter painted the darkness.” In an essay published in Women’s Studies Quarterly that appears later in different form as “From the Poets in the Kitchen,” Marshall praises the working-class black, Caribbean women who talked around the kitchen table when she was a child. Crediting these women as her first literary inspiration, Marshall focuses on their intelligence and their creativity with language – not on the many isms that threatened them at every turn. According to Marshall, these black women’s “laughter which often swept the kitchen was, at its deepest level, an affirmation of their own worth; it said they could not be. defeated by demeaning jobs...” Black women’s laughter, on the page and in life is often loud and unabashed: what some might call vulgar or uncouth; what some of us call home. Take a moment and listen…if you’re a black woman, if you know black women intimately, then you can hear the shades of these different laughters percolating now. But if you don’t know black women, or if you want a reminder, look to the pages of Paule Marshall for black women’s laughter. Five Steps You Can Take to #CiteBlackWomen Now: Tips for the New Academic Year - Christen A. Smith8/22/2019  The beginning of the new academic year is a crucial time. It’s the time to write new syllabi and revise old ones, make semester plans and embrace new possibilities. Here are some easy and steps you can take to #CiteBlackWomen. 1) Read our work. Read Black women’s scholarship. Don’t know of any? Ask and do some research. Once you’ve found Black women’s work, deepen your understanding of it and seriously engage the ideas. Black women literally publish in every areas imaginable. All you have to do is find us. 2) Integrate our work in a serious way. Don’t just slap us onto your bibliography—critically engage us. For example, if you are teaching a class on urban landscapes, don’t just add a Black women’s book on cities to your class. Ask students to think about how Black feminist geographies change our perspectives of space. We aren’t just sources of information: we are also theorizers and innovators. 3) Acknowledge our work. Once you’ve incorporated us into the structure of your class/bibliography, acknowledge our work. How have we uniquely changed/impacted the field? Say our names out loud. Don’t just paraphrase what we’ve taught you and pass it off as your own intervention. Like that idea, let us know who inspired it. 4) Let us speak. Give us the space and time to speak. Assign a Black women’s work? Invite her to speak on your campus. Invite her to speak in your class (*and PAY her!). Support her by inviting her by attending her conference papers and/or talks. Make space in your daily practices to ensure that Black women’s ideas are heard. Cite us in your lectures, your talks, meetings, even casual conversations. It makes a difference. 5) Let us breathe. Finally, let us breathe. We do a whole lot. Most of us work 3-4 shifts not just 2 (a la the 2nd shift). Don’t overwork us. Give us break. Give us the space to be quiet, write, reflect, laugh, cry, be. And don’t take it personally when we need time away. If you do these five things you are on a path to change. Just keep them in mind and you can make real progress this semester and beyond. Good luck. P.S. - Thoughts for Black Women And p.s. thoughts for Black women particularly: most of us were deliberately taught NOT to value Black women’s work in graduate school. We were literally instructed to cite white men and we were/are often punished for not doing so in school and beyond. It is not easy unlearning this. It is often triggering as we have been shamed and disciplined into thinking that our own knowledge production is unworthy of citation. Be gentle with yourselves as you unlearn erasing Black women. Seek allies and sister-friends that can support you in your journey to value yourself and your fellow Black women. Take the courageous step to deconstruct your own habits and recognize this is a PROCESS not zero sum game. You can do it. And support your sisters as they go through this process as well. The last thing we need is more hate and negativity. Be kind and patient with yourself and others. |

Archives

October 2021

Categories |

Proudly powered by Weebly

RSS Feed

RSS Feed