|

3/30/2020 2 Comments “The Hand of Cleanliness”: Black Women and the Politics of Domestic Work During the Coronavirus Crisis - by Luciana Brito, Ph.D. On March 19th, the metropolitan region of Rio de Janeiro announced its first death from the COVID-19. She was a 63-year-old hypertensive and diabetic domestic worker who was taking care of her employer, a 62-year-old woman who lives in the upscale Leblon neighborhood of Rio de Janeiro. The employer had just arrived from Italy—one of the countries hardest hit by the virus so far—and did not advise her domestic worker that she was sick. Although the woman was in isolation after her trip (“selective confinement”), she still relied on her domestic worker to come in, clean and take care of her—an aspect of social distancing that few are discussing. As the Coronavirus pandemic paralyzes the world, poor Black women in Latin America are particularly vulnerable to the disease and no one seems to care. At first, it seemed as if Coronavirus was primarily impacting the white, the rich, and the elite. Yet, over the past week, stories out of Brazil reveal the vulnerability of those who take care of those who are infected (with our without symptoms) beyond hospitals. In Brazil, Black women disproportionately work as domestic workers, and domestic workers are particularly vulnerable, and invisible in our discussions of the dangers of the disease. Several recent cases across Brazil reveal the risk that domestic workers face. A businessman from Rio de Janeiro received the news from his doctor that his test was positive for CODVID-19 by telephone. The man infected was in a steakhouse, surrounded by friends and his wife, who was later infected as well. Although the two went into isolation, their maid-- the only person who lives with the couple, and who now works in "gloves and masks"-- did not count as someone that should be put in isolation. In Bahia, my home state in Brazil, this pattern repeats itself. The first case of a person infected was in the city of Feira de Santana. The first person infected, a 34-year-old womanreturned to Brazil from Italy carrying the virus with her. She was tested for the virus in a private hospital. However, despite orders to remain "in isolation", and monitoring by the state health secretary, the woman’s42-year-old domestic workeralso became infected. The domestic worker’s 68-year-old mother became the third infected. Historically, Black women have been the hands that clean up after the world. However, recently two trends have made this work more precarious. On the one hand, neoliberalism has continued to devalue domestic, leading to less stability and continued low pay. On the other hand, austerity measures have meant that funding for cleaning at the state level (in schools, universities, public places) has been cut drastically in places like Brazil, putting us all at risk. There is a direct connection between austerity, the risk we face with public hygiene, a reduction in public services like funding for university education, and the vulnerability of domestic workers. Here in Brazil, our university campuses get dirtier by the day. In 2016, the federal government cut public spending and investment in health care and education drastically. One of the first signs of this cut was the outsourcing of cleaning staff. Composed mostly of Black workers, government-contracted cleaning teams that were not fired became overloaded by extra shifts and extra work. Now, as the world waits for a Coronavirus vaccine, personal hygiene and aggressive cleaning of public spaces are the most effective way to fight the proliferation of the virus. Most often this means that our health and our very lives are in the hands of the domestic workers who clean our public and private spaces—and across the Americas that frequently means Black women. Last Saturday I was on the campus of the Federal University of Bahia and one of the bathrooms was spotless. A Black worker, alone, almost compulsively cleaning the men's and women's bathrooms at the same time. Yet while this one woman was working above and beyond to try to keep us safe, at my campus outside of the city limits, the bathrooms remain dirty because the workers who once cleaned them have been laid off. My university, the Federal University of Recôncavo da Bahia, has suffered from recent federal government cuts in education. Most of the classrooms smell like mold and have no ventilation. Oftentimes we do not have running water or hand sanitizer. Undervaluing domestic work has a direct impact on our health. Cleanliness has a race, gender and class. The other day I was watching a popular news program. One infected and isolated interviewee said, "The worst thing about quarantine is having to cook your own food." Another claimed that she had never imagined herself infected with a virus like this. In other words, many of the privileged elite who contract the virus believe that getting sick from epidemics is a thing of the poor. It is as if it were an “uppity virus" , that blindly disrespects social hierarchies, throwing everything upside down. What did the privileged expect from this pandemic? They expected COVID-19 to be like dengue fever, zika and chicungunha-- “poor people’s” diseases that afflict spaces neglected by the state (these diseases are linked to basic sanitation issues like access to clean, running water). When poor and Black people were the disproportionate victims of rabid disease, no one seemed to care. Now that the white elite are particularly in focus, the sense of social responsibility has shifted, yet Black women still remain particularly at risk. Domestic workers depend on Brazil’s university health care, use public transportation, live with their families daily, and cook their own food. Many of them work informally and do not receive sick leave or qualify for unemployment should they have to stay at home. What happens when their kids' schools close? Are they allowed to stay at home? If isolation means that infected people are distant from other people, why don't they count? It is time for us to consider the race, gender, class dimensions of this global pandemic. * Credits: A mão da limpeza (The Hand of Cleanliness) is a composition by Gilberto Gil and is on the album A raça humana - The human race, which by the way is very relevant for the moment and we should listen all these days that we are at home… for those who can afford to work From home. Luciana Brito is an historian, member of the Black Women's Network of Bahia, and identifies herself as a black intellectual and working-class feminist. She is a professor in the Department of History at the Federal University of Recôncavo da Bahia-Brazil, specializing in the history of slavery and abolition in Brazil and the United States. She is also interested in the areas of race, gender and class in the Americas. She is the author of several articles and the book Temores da África, which will soon be published in English. Instagram: @lucianabritohistoria

2 Comments

On Friday, March 6th, I had the pleasure of interviewing two prolific scholars in the field, Drs. Daina Ramey Berry and Kali Nicole Gross on their most recent coauthored book, A Black Women’s History of the United States(Beacon Press, 2020). As a history graduate student, I am always thinking about the gaps in the literature including the underexplored topics, so when I asked Drs. Berry and Gross if their work was picking up on themes that they thought were missing from the previous generation of historians, their response problematized my original question. Instead of approaching the field of Black Women’s History through the lens of critique, they informed me that they were interested in showcasing how the scholarship has evolved over the last two decades. It was not that pioneering historians like Paula Giddings, Deborah Gray White, Darlene Clark Hine, Sharon Harley, and Evelyn Brooks Higginbotham lacked analytical substance. Rather, the newer generation of scholars are asking different questions and developing innovative methods to recover black women’s voices in archives bent on erasing us. Drs. Berry and Gross remind us that we stand on the shoulders of black women historians who labored before us, and as we expand the field, it is necessary to acknowledge and cite their foundational works. A Black Women’s History of the United States traces our history in the Americas from before slavery to our central role as the backbone of contemporary movements against persisting injustices. In writing such an expansive survey of Black women’s history, Drs. Berry and Gross discussed the process of collaborative work. They highlighted the manuscript workshop with their “Sister Scholars” in the field, and how it was through consulting with other black women historians that they received feedback and suggestions on themes and approaches for the book. For example, from the Sister Scholars workshop, Drs. Berry and Gross got the idea to start each chapter with a narrative of a black woman’s experience to correspond with a new periodization. In these anecdotes, we learn about figures that disrupts traditional histories of the U.S. like Isabel de Olvera, a free woman of African descent, who migrated to the U.S. before 1619. And even others, such as Aurelia Shines, a black woman who challenged Jim Crow’s segregation laws by refusing to give up her seat in 1948, seven years before the infamous Rosa Park’s protest in Montgomery. While their work foregrounds the ways black women navigated the double oppression of race and gender, Drs. Berry and Gross’ analysis refuses to place our history as purely oppositional or only existing to combat white supremacy. Instead, A Black Women’s History of the United States accounts for both black women’s resistance and liberation struggles, and their leisure activities through travel, art, and the erotic. Drs. Berry and Gross helps us rethink black women’s intellectual labor as a collective, which reframes our professional pursuits. As we move in a space like the academy that is designed to monopolize and capitalize on our movement and labor, Drs. Berry and Gross reminds us of the important role community play in surviving and confronting such exploitation. It is in the collective that we liberate ourselves from the individualistic, “clout-chasing,” performative aspects of academia. This collectivity prompts us to continue organizing conferences, workshopping our research, and building professional and mentorship relationships. I am grateful for the opportunity to have had a conversation with Drs. Berry and Gross about their new book, and I am sure this text will ignite a new generation of scholars to continue to do the work. Tiana Wilson is a third-year doctoral student in the Department of History with a portfolio in Women and Gender Studies, here at UT-Austin. Her broader research interests include: Black Women’s Internationalism, Black Women’s Intellectual History, Women of Color Organizing, and Third World Feminism. More specifically, her dissertation explores women of color feminist movements in the U.S. from the 1960s to the present. At UT, she is the Graduate Research Assistant for the Institute for Historical Studies, coordinator of the New Work in Progress Series, and a research fellow for the Center for the Study of Race and Democracy. Check out Tiana Wilson's interview with Profs. Daina Ramey Berry and Kali Nicole Gross for the Cite Black Women Podcast.

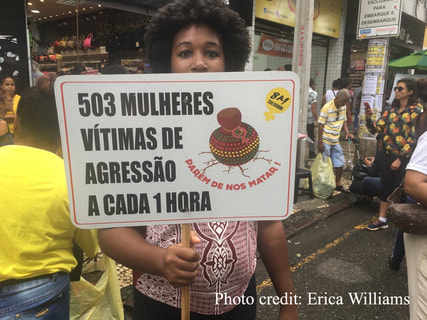

This past July I was in Salvador to do research on black women’s activism during the month of Julho das Pretas(July of Black Women), which Odara – Institute of the Black Woman started seven years ago. Julho das Pretas was initially launched as a way to bring attention to July 25 – the Dia Internacional da Mulher Negra da America Latina e o Caribe (International Day of the Black Latin American and Caribbean Woman). July 25th has been celebrated since 1992, when a group of women organized the first Encontro de Mulheres Negras Latinas e Caribenhas in Santo Domingo, the Dominican Republic, and created the Rede de Mulheres Afro-Latino-americanas e Afro-Caribenhas.[1]Thus,Julho das Pretaswas seen as a way to celebrate black women and raise awareness about the issues facing black women for the entire month of July. Julho das Pretas has now spread all over Brazil. On July 25, 2019, black women gathered in major cities all over Brazil for the Marcha das Mulheres Negras. I was able to attend the Marcha das Mulheres Negrasin Salvador, Bahia, which had the theme: Mulheres Negras por um Nordeste Livre Do Racismo, da Violencia, e pelo Bem Viver(Black Women for Northeast Free of Racism, Violence and for Good Living). On the Facebook page for the march, the organizers wrote, “the march will bring together plural black women, to shout out against racism, violence, femicide, LGBTphobia, maternal mortality, obstetric violence, the genocide of black youth, religious and environmental racism, against welfare reform, cuts in education and all forms of fascist and white supremacist oppression and ignorance in force in national politics.”[2] We gathered in Piedade plaza starting at 1pm.Staff members from Odara kicked off the march by welcoming everyone to the march, and inviting people to share their thoughts with the crowd on the open mic. Milca Martins, Secretary of Sindoméstica, the union of domestic workers, spoke out about the urgency of black women saying NO to all the various forms of violence that they suffer. Hailing from the peripheral neighborhood of Mata Escura, she encouraged everyone present to form women’s groups in their communities, and to work with women from periphery. She even brought women from Mata Escura with her to the march, for whom it was their first time participating in the march. Martins pointed out that the first to be hit by the recent controversial welfare and retirement reforms of are black women. She got emotional when speaking about the unjust situation in which black women domestic workers often find themselves in – “the system is killing our kids and they ask, ‘where’s you mom?’ And we are working taking care of white children and don’t have anywhere to leave our children!” After Milca Martins’ speech, Odara staff members gave rousing speeches with lots of neighborhood shout outs. There were multitudes of black women of all ages gathered in the plaza. A capoeira group called Sonho do Zumbi performed, with mostly women capoeiristas jogando (playing). People went up and read poetry. The sisters of the Irmandade de Boa Morteopened the march as a symbolic act of reverence to what Afro-Brazilians call “ancestralidade.” The literal translation of the word is ancestry, but it is much more than family or genetics – it has to do with African cultural heritage, practices, aesthetics, and religiosity that has fortified Afro-Brazilians and given them the strength and fortitude to resist enslavement, colonization, and continued racism and oppression in Brazil. Ironically, while the Odara staff were asking for people to clear a path to allow the elder black women from Boa Morteto open the march, the media swarmed in front of the irmãs, with journalists sticking microphones in their faces and trying to get interviews with their video cameras. It was a tense and awkward moment in which the media clearly was acting in their own interest, but ironically, holding up the progress of the march! When the march did get under way, it was marvelous. The mic was open the entire time as we walked down to Cruz Caída in Pelourinho. Two black trans women spoke out about how transwomen and travestisare also a part of the black women’s movement, and how they are especially vulnerable because they are often locked out of the job industry due to their gender identity. At some point, it began raining – first a sprinkle, and then it poured. The crowd dispersed a bit around Praça da Sé, but the rain did not dissipate the energy of the march. Once the rain passed, the crowd regathered and continued onward. That felt symbolic to me, somehow. Much like the struggles that black women face, we protect ourselves from the rain, but then regroup, find strength and solidarity amongst our sisters, and continue on our way. In this Instagram post advertising the March, it says “For a Bahia free of Femicide” and shows women holding signs about the high rates of violence against women. The signs claim that there are 5 beatings of women every 2 minutes and 1 woman murdered every hour two hours. Notably, a disproportionate amount of victims of this type of violence in Brazil are black women. On November 27, the news of yet another femicide of a young black woman with a promising future rocked the black feminist activist community of Salvador. Elitânia Souza da Hora was a 25 year old student in Cachoeira, Bahia, and a quilombola leader who was murdered by her ex-boyfriend. The tragic irony is that she was preparing to defend her undergraduate thesis on the topic of femicide, and then she became a victim of it. In the spirit of citing black women in transnational contexts, I want to share my translation of the Nota de Repúdio from the Forum Marielles de Mulheres Negras de Salvador. FROM MARIELLE FRANCO TO ELITÂNIA SOUZA DA HORA: WHO CARES ABOUT THE LIVES OF BLACK WOMEN? December 1, 2019 English Translation By Erica Lorraine Williams On the afternoon of November 22 of this year, a Babalorixá from the city of Santo Antonio de Jesus, in the Recôncavo of Bahia, sent me a Whatsapp message distressed. He said he was going to do an activity in his religious house on December 1, and invited me to a roundtable discussion on the topic of “Femicide,” which he had chosen at the behest of a deity. The gods were worried about the violent occurrences that had been affected women of the city. On November 27, we were horrified by the news that Elitânia Souza da Hora was cruelly murdered when she left her classes at the Federal University of the Recôncavo of Bahia (UFRB), in the city of Cachoeira, Bahia. A brilliant young black woman, she was a quilombola leader who worked for an NGO of the valorization of the culture of the Recôncavo Baiano. She had her whole future ahead of her. She was going to graduate with a degree in Social Services and she was part of CASSMAF, the Academic Center of Social Services Marielle Franco. Like many women in Brasil, Elitânia da Hora found herself trapped in an abusive relationship with a man who wouldn’t leave her in peace. A victim of domestic violence, she had already reported the case to the police station, and she even had a protective order against the ex. She was a woman with a big smile, always nice and kind, with strong opinions and dreams of a successful professional life. On the other hand, the brutal assassination of Marielle Franco last year also shocked us and, as the case has unfolded, the way the Brazilian system of justice has handled this heinous crime continues to frighten us. The high rates of femicide in Brasil are also scary particularly when we analyze them from a racial dimension. According to data from the Ministry of Health compiled by the Atlas of Violence, launched by the Institute of Applied Economic Research (Ipea) and by the Brazilian Forum of Public Security (FBSP), for example, 4,936 murders of women were registered in 2017. That is an average of 13 homicides per day, the largest number in a decade! According to information from the Map of Violence, in Brazil between 2003 and 2013 the number of femicides of black women jumped from 1,864, in 2003 to 2,875 in 2013. In contrast, there was a decrease of 9.8% in crimes involving white women, which fell from 1,747 to 1,576 between the years. The death of Marielle Franco added to this statistic. And it was from the idea of honoring the council woman from Rio de Janeiro, that the Fórum Marielle of Salvador-Bahia was created, with the objective of encouraging the candidacies of black women in spaces of power, because we recognize that such women find themselves under-represented in these spaces, even as they make up the majority of the Bahian population. Since its creation on March 14, 2019, we have gathered to discuss various topics of interest of black women and we have perceived the strength and potency of the diverse organizations of black women that make up the Forum. However, femicide remains untouchable for us black women, as a constant threat to the lives of these women and to their well-being. The death of Marielle Franco also made this complaint, therefore our goals as a Forum that brings together dozens of organizations of black Bahian women is also to fight against this necropolitics adopted by the Brazilian state, that has a tragic impact on the well-being of black women, we want to denounce and unite in diverse fronts of confronting this extermination. Many organizations of women have long been engaged in this fight against the genocide of black people and against femicide. In Bahia, we have for example the Campaign Parem de Nos Matar(Stop Killing Us), organized by the Bahian Network of Black Women o, the Community Forum to Combat Violence which develops several actions and a vigil every month in Lapa station in Salvador, collectives like Mahin – Organization of Black Women, that carries out actions with women in situations of violence in peripheral neighborhoods, and Odara – Institute of the Black Women, that also has a campaign on this theme, among other organizations and collectives across the state of Bahia. The state government, in its turn, also possesses secretaries and other organs of the justice system that deal with this issue, but they seem dead to us, at least with regard to the deaths of black women, since in this group femicide has increased, demonstrating that the policies appear to be effective for white women, but not for black and brown women. The state can’t even guarantee what the law advocates, for in the case of the Rio de Janeiro Council Woman Marielle Franco and of Elitânia Souza da Hora, the young Social Services student at UFRB, the state failed and wasn’t able to offer the protection that they needed, not even through complaints nor in the guarantee of the protective order, nothing prevented the monstrous murderer from taking the life of Elitânia, a young black quilombola woman, active in the student movement and in defense of affirmative action policies. We of the Fórum Marielle denounce this and we put ourselves on the alert in the face of so much neglect, and we demand answers of the appropriate instances, we will speak up, denounce, and demand our rights, so that all black women may live their lives without being interrupted! FORUM MARIELLES DE MULHERES NEGRAS DE SALVADOR [1]http://www.palmares.gov.br/?p=54714 [2]A marcha reunirá mulheres negras plurais, para gritar contra o racismo, a violência, o feminicídio, a LGBTfobia, a mortalidade materna, a violência obstétrica, o extermínio da juventude negra, o racismo religioso e ambiental, contra a reforma da previdência, os cortes na educação e todas as formas de opressão e ignorância fascista brancomachocêntrica em vigor na política nacional.  Dr. Erica L. Williams is Associate Professor and Chair of Sociology and Anthropology at Spelman College. She is also a member of the Cite Black Women Collective. Her full bio is available on our Collective members' page on this site. |

Archives

October 2021

Categories |

Proudly powered by Weebly

RSS Feed

RSS Feed